What Events in the 1930 and 1940 Led to the Moderism Art Movement

Culture and Arts during the Depression

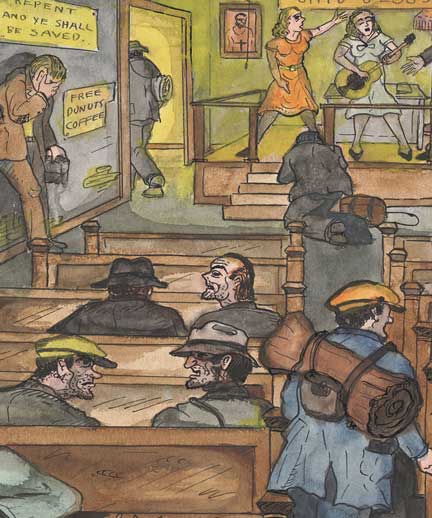

The Low led non only to new arts funding, but a radical rethinking of how to express the social experience of the Depression itself. "Mission House, Skid Route, Seattle, Launder. 1930," watercolor by Ronald Ginther. (Property of Washington State Historical Social club, all rights reserved.)

The 1930s were a menstruum of intense creative experimentation, as new forms and methods were explored, transformative cultural institutions were founded, and artists self-consciously sought to accomplish broader layers of the public. The ascent of social unrest during the Low heightened the political concerns of artistic works, while New Bargain programs gave artists both federal recognition and the funding and infinite to work out new cultural forms. Technical changes, similar the popularization of the radio, changed how accessible culture was and to whom, and an international break from formalism and modernism likewise worked to produce a popularized, socially conscious tendency in American art. During the Depression decade, Washington State, ofttimes seen as marginal to national art history, hosted some of the most innovative theatre, musical, and performing arts work in the nation, with sometimes global resonance.

It is 1 of the ironies of the Slap-up Depression that the allegorical cultural institution of Washington Land, the Seattle Art Museum, was created and privately funded during the darkest days of the economic crunch, when tens of thousands were losing jobs and homes. SAM was a gift to the city from art collector Richard Fuller and his wealthy female parent Margaret Fuller. In 1931, they hired UW architect Richard Gould to blueprint a museum sited in Volunteer Park and pledged much of their personal fine art drove to the city. The building, which now houses the Seattle Asian Art Museum, opened to the public in 1933.

The SAM story reminds usa that non everyone suffered or even lost money during the Low and reminds u.s.a. too that philanthropy accelerated in the 1930s, as some of those who retained wealth gave to charities to aid the unfortunate and others gave to the arts to rescue cultural institutions that struggled among the economical decline.

Merely more important than philanthropy was the new role that regime funds and government programs would play after 1933. For the first time in American history, art was deemed worthy of public support, and New Bargain federal dollars enabled an explosion of artistic endeavors, from painting to music to theatre to compages. The 1930s would prove to be a pivotal decade for Washington Country'southward arts and culture, leaving the region with new institutions, lasting artistic accomplishments, and a new public understanding that art was no longer only for the wealthy.

Cornish College

Washington's cultural ferment of the 1930s and the New Bargain era would not have been possible without the existence, decades before, of smaller institutions and artists collectives, most notably the pocket-sized and struggling private Cornish College of the Arts, in Seattle. Founded every bit a music schoolhouse in 1914 past Nellie Cornish, the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle grew to comprehend all the performing and visual arts, and served equally the eye of the Northwest'south growing art scene. Despite its financial and social ties to the more traditional Seattle Fine Arts Social club, and the sometimes-conservative leanings of its Board of Directors, Cornish as well hosted performing artists who were breaking from traditional forms and experimenting with new modes of performance, presentation, and style.

From a glance at the list of kinesthesia and students during the 1930s, information technology is clear that Cornish was a seedbed for both regional likewise as national cultural transformations during the Depression years: mod dancer Martha Graham taught at Cornish in the summertime if 1930 and was deputed to give a solo Seattle performance; innovative composer John Cage taught at the school and developed his "prepared piano" at that place in 1938; Seattle native Merce Cunningham began his dance training at Cornish in 1937-1939, and was discovered there by Martha Graham, who promoted his career in New York; and hosted Northwest native and modernist photographer Imogen Cunningham as an creative person-in-residence in the late 1920s; and Florence and Burton James began their theatre experiments as kinesthesia at Cornish before founding the Seattle Repertory Playhouse. [1] The "Northwest School" of painters—Morris Graves, Marker Tobey, Guy Anderson, and Kenneth and Margaret Callahan—based at Cornish and in the rural Skagit Valley, sought out a new aesthetic that combined natural forms with the influences of Asian fine art, and added some other dimension to the innovations of 1930s and 1940s culture.

Cornish School of Music in 1920, downtown on Broadway and Pino, before relocating to Roy St. on Capitol Hill. Nellie Cornish founded the school in 1914, and it functioned equally a middle of new arts movements in Seattle. (Photo courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)

With the market place crash of 1929, the drastically contracted market place for the arts and lack of money for patronage may take prompted some of the independence and radical revisions of creative forms and new visions of what music, images, and movement could be. As Kenneth Callahan, a member of the loose Northwest Schoolhouse and assistant manager of the Seattle Art Museum wrote in 1936, "Since 1929 artists, for the greater role, accept come to the realization that in that location is no longer a marketplace for their output. Whereas formerly artists attempted to run across, interpret and execute their work and way that conformed to the tastes of the moment, many thereby making a fair living, today the situation is very unlike… [T]here is lilliputian actual buying of the art of contemporary artists. Equally a result, more than and more than painters are devoting themselves to problems of painting, crafts, and interpretation." [2]

New Deal Arts Funding

As part of the public relief programs of the New Deal, artists, musicians, actors, and writers were employed past the federal government in an array of projects designed to create jobs. These programs started in a modest fashion in 1933 and and so became more common after 1935. Piece of work relief was one of the goals, but leaders of these programs often also hoped to sponsor ethnic, regional talent and encourage the growth of a national, pop artistic culture. The guiding philosophies of the Federal Fine art, Federal Theatre, Federal Writers', and Federal Music Projects (all 1935–1939) promoted publicly engaged and publicly accessible arts. New ideas about the social responsibilities of artists and new styles and subject matter—conveyed by the artistic label "social realism"—were office of this artful transformation.

The artistic legacy of the New Deal can be seen today in the murals that adorn public buildings throughout the state, including schools, libraries, and mail offices. Hundreds of artists worked on these murals, which in the spirit of the time, were usually painted in a realistic style and depicted groups of men and women working together in common cause, either in 1930s contemporary scenes or in re-visions of the past history. See Visual Arts in the Cracking Depression, a special section of this website.

The painters of what became known as the Northwest Schoolhouse worked in a different aesthetic, often interested more in nature than people, exploring the light and color of the Puget Sound with tones and techniques strongly influenced by Japanese creative person traditions. They would requite the region its kickoff widely recognized artistic movement—minor in the scheme of American art history—simply an important contribution to regional pride and forth with Cornish (where several taught) a cistron that would, in the time to come, attract artistic talent to the region.

William Cumming may be the most pregnant of the new artists of the Smashing Low. A protégé of the Northwest School, he veered dorsum and forth between modernism and social realism, committed to what biographer Matthew Kangas calls "the image of event, that is, subjects that ordinary people could chronicle to in their own lives, images that could resonate without the taint of moralizing propaganda." [3]

Propaganda was precisely the purpose of two other artists who take left u.s.a. riveting images of street life and political activism of the 1930s. Woodcut artist Richard Correll began illustrating the Seattle Communist Party's newspaper, the Voice of Action, producing a new artistic fashion and political statement with broad entreatment. Indeed, Correll's work became so popular that he began teaching woodcutting classes. Dark, powerful, and complex, his remarkable graphics tell stories of strikes and struggles for economic and social justice. [4]

Ronald Ginther painted in obscurity throughout the 1930s. A self-taught artist who worked with ink and watercolors, his collection of more than 80 vividly colored scenes are a unique resources, depicting the rough life of Hoovervilles and homeless men, of jails and soup kitchens, unemployed demonstrations and police attacks, strikes and radical protests—all of which he knew well.

Theatre, Photography, Music, Film

As discussed in Theatre Arts in the Great Low, a special section of this website, Washington'south partitioning of the Federal Theatre Project was i of the nation'south most successful and extensive programs that drew on erstwhile Northwest theatre traditions like vaudeville as well as Depression-era civil rights concerns to shape its programs. Washington State's Federal Theatre Projection included a traveling vaudeville company, the all-African American Negro Repertory Company, a Children's Theatre, and produced "Living Newspapers" that dramatized regional current events.

Seattle's jazz civilisation flourished in the 1920s and 1930s, peculiarly in the multiracial neighborhood culture of Jackson Street in Seattle's Central Commune. Pictured hither is Edythe Turnham and her Knights of Syncopation, c. 1925. Turnham toured the Northwest with her band and played up and down the West Coast and on President Line Cruises, embodying travel routes that linked Washington musicians to the residue of the nation and the country. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library Digital Collections.)

Washington's Depression was too the bailiwick for two famous American artists who lent their talents to promote federal projects, mingling their own social and artistic concerns—sometimes uneasily, sometimes happily—with the needs of the New Deal government. Dorothea Lange, whose photographs of California'due south Depression migrants have become iconic images of the Depression, photographed migrant subcontract laborers in Washington's Yakima Valley in 1939—too as the after Japanese American internment camps—for the Subcontract Securities Administration. Folksinger Woody Guthrie was deputed to write songs promoting public utilities and work relief-built dams on the Columbia River, producing 1941's "Roll on, Columbia," the current land vocal.

The Depression years likewise saw Washington's emergence in national films, as the major Hollywood studios set and filmed many major 1930s films in the State'southward mountains and waterfronts. Washington'southward mountains served as cheaper stand-ins for the Alaskan Yukon, while scenes of Seattle'due south waterfront provided authenticity and novelty to Hollywood's films. State boosters used the films as ways to bring tourism to the State, while Hollywood sometimes employed Washington's unemployed as temporary film crews.

Symphonic music suffered during the Great Low. Seattle had an undistinguished, mostly volunteer symphony at the start of the decade and despite support from the Federal Music Projection, that establishment and other local symphonies would struggle for audiences throughout the decade. Radio was part of the trouble for the symphony, but office of the popularization of art in the era: radio networks at present delivered music of many kinds straight into the family living room at no cost.

Greek clarinetist Nicholas Oeconamacos, who had performed under John Philip Sousa and the Seattle Symphony conductor Homer Hadley, returned to Seattle during the Great Depression to play for change on the street. Federal and regional funding also provided aid for unemployed musicians, and the City Council sponsored outdoor concert serial in the parks as one manner to employ musicians. (Seattle PI photograph, 1931, courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)Bands playing popular music in clubs and dancehalls also struggled in the early 1930s, but with the end of prohibition in 1933, going to clubs became very popular for those who could afford it. Equally Jazz evolved into Swing Jazz, dancing became the rage. Jackson Street, the heart of Seattle'south blackness community, was also the heart of the region'southward Jazz scene. Local bands played the Jackson Street clubs and attracted mixed black and white audiences, while touring big bands found larger venues downtown where simply whites were allowed.

Equally information technology was in the rest of the country, the Depression-era arts in Washington State both chronicled people's experiences and gave voice to a particular vision, built-in of economic crunch, of social change and renewal. The combination of federal arts funding through the New Bargain and the stimulation of social movements for ceremonious rights, industrial unionism, and social reform created a new cultural environment, new forms of fine art, changed understandings of community and private social roles, and a plummet of distinctions between fine art, civilization, and politics.

Copyright (c) 2009, Jessie Kindig

Next: Visual Arts in the Nifty Depression

Click on the links below to read illustrated research reports on culture and the arts during Washington's Low.

| Ronald Ginther Watercolors Ginther produced more than eighty paintings. They are a unique resource, depicting the rough life of Hoovervilles and homeless men, of jails and soup kitchens, unemployed demonstrations and law attacks, strikes and radical protests. |

| The Power of Art and the Fear of Labor: Seattle's Production of Waiting for Lefty in 1936, past Selena Voelker The Jameses founded the Seattle Repertory Playhouse and played a crucial role in the development of the Federal Theatre Project in the land, as well as reimagining the role of theatre in Washington. |

| Escape to the Movies: Seattle Cinema in the Great Depression, by Andrea Kaufman Flick houses found a variety of ways to bring people to the movie theatre during the Depression, from special bargain nights and promotions to new escapistf flick genres. |

| When Hollywood Went to Washington: Film's Golden Age in the Evergreen State by Zachary Keeler Hollywood and Washington State formed a mutually beneficial relationship during the 1930s, as Hollywood films brought tourism and job opportunities to Washington and used its settings to portray the Alaskan Yukon or to stand in for the rural W. |

| Jazz on Jackson Street: The Birth of a Multiracial Musical Community in Seattle, by Kaegan Faltys-Burr Seattle'southward jazz scene flourished in the 1920s and 1930s, peculiarly in the multiracial neighborhood culture of the Key District and Jackson St. |

| Dorothea Lange essay series: Social Documentary photography Dorothea Lange visited Washington's Yakima Valley in 1939 to relate rural farm life and migrant families during the Depression. • Part one: Dorothea Lange'southward Social Vision: Photography and the Swell Depression, by Emily Yoshiwara• Part 2: Dorothea Lange in the Yakima Valley: Rural Poverty and Photography, by Stephanie Whitney |

| Dorothea Lange's Yakima Valley Photo Gallery |

| Richard Correll and the Woodcut Graphics of the Voice of Activeness, by Brian Grijalva Seattle'south Communist Party newspaper relied on woodcut creative person Richard Correll for many of its illustrations. Correll art was stark and unforgettable. He could narrate a strike or particular a militant political position in a single 4 inch by 5 inch image. |

| The 1932 Seattle Sports Scene: Helping the Emerald City through Difficult Times, by Brian Harris Seattle rallied effectually its sports teams and prospective Olympic athletes equally a symbol of community life and leisure during the Depression, despite loss of funds for many sports programs. |

| The Rainy City on the "Wet Coast": The Failure of Prohibition in Seattle, by Kayta Katherine Samuels Prohibition failed to control the product, consumption, and enjoyment of alcohol in Seattle and the unabridged "wet declension." |

Visual Arts | |

| Federal Art Project in Washington Land The most ambitious of the New Deal visual arts programs, the Federal Art Project emphasized piece of work relief for artists as well as public pedagogy and documentation of folk traditions. In Washington State, information technology employed dozens of men and women in diverse pursuits such every bit easel painting, landscape painting, sculpture, teaching, model making and more. |

| Public Works of Art Projection in Washington Country The beginning visual arts program launched during the Great Depression, the Public Works of Art Project employed more 3,000 artists nationwide including 50 in Washington State. It established an important precedent regarding federal regime support for the arts and served as a model for later on initiatives. |

| Mail Office Murals and Fine art for Federal Buildings: The Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture in Washington State Centrally managed past the Treasury Department in Washington, D.C. the Section commissioned thousands of murals, wood carvings and sculptures for public buildings, including postal service offices, court houses and federal agency headquarters in the capital. Every bit a result of its presence in small and large communities, this programme'south work is perhaps the best known of any New Deal visual arts initiative. |

| New Deal Post Office Murals in Washington State This google interactive map marks the location of the 18 Washington State mail service offices that housed art commissioned by the Department. Common motifs include agronomics, logging and western history, featuring images of both Euro-American settlers and Native peoples. For more information on the Treasury program, please see the research report "The Section of Painting and Sculpture in Washington State," |

| The Spokane Fine art Heart: Bringing Fine art to the People In addition to providing gainful employment to thousands of unemployed artists, the Federal Art Project (FAP) also stressed fine art education through customs art centers as one of its master objectives. One of the most successful sites, hosting lthousands of visitors and hundreds of classes, was located in Spokane, Washington. |

Theatre Arts | |

| Federal Theatre Project in Washington Land, by Sarah Guthu The FTP in Washington was one of the most vibrant in the land, including the Negro Repertory Unit of measurement, Living Newspaper theatre journalism, a Children's Unit of measurement, and hosted traveling productions to New Bargain public works programs effectually the state. |

| Seattle's Negro Repertory Company: Outside of New York City, Washington's FTP hosted the only all-African American company in the nation, who produced three plays: Stevedore, about a longshore strike; an all-black production of Lysistrata, which was closed down for its "scandalous" scenes; and a product written by the Negro Unit based on the life of poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. • Stevedore , by Sarah Guthu• Lysistrata, by Sarah Guthu • An Evening with Dunbar, by Sarah Guthu |

| The Jameses and the Playhouse, by Sarah Guthu The Jameses founded the Seattle Repertory Playhouse and played a crucial role in the development of the Federal Theatre Projection in the state, equally well as reimagining the role of theatre in Washington. |

| Living Newspapers: These productions combined theatre with journalism, and brought regional controversies to life, including battles over public and private power; the regulation of syphilis; and immigration. • Power, by Sarah Guthu• Spirochete, by Sarah Guthu • One Third of a Nation, by Sarah Guthu |

Notes

[1] Richard C. Berner, Seattle, 1921–1940: From Boom to Bust (Seattle: Charles Press, 1992), 247–251; Cornish Higher of the Arts, "Making History," <http://www.cornish.edu/most/history/>.

[2] Callahan'due south review quoted in Berner, Seattle, 1921–1940, 248.

[three] Matthew Kangas, William Cumming: The Epitome of Consequence (Seattle: Charles and Emma Frye Art Museum, 2005), p. 15.

[iv] Brian Grijalva, "Richard Correll and the Woodcut Graphics of Voice of Activity," Communism in Washington Country History and Memory Project, <http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/cpproject/correll.shtml>.

Source: https://depts.washington.edu/depress/culture_arts.shtml

0 Response to "What Events in the 1930 and 1940 Led to the Moderism Art Movement"

Post a Comment